Related Categories

Related Articles

Articles

Behavioral Finance

(Definition #2)

Let's examine how Behavioral Finance compares to conventional finance, introduce you to three important contributors to the field and take a look at what critics have to say.

But why is behavioral finance necessary?

When using the labels "conventional" or "modern" to describe finance, we are talking about the type of finance that is based on rational and logical theories, such as the capital asset pricing model (CAPM) and the efficient market hypothesis (EMH). Main assumption there: These theories assume that people, for the most part, behave rationally and predictably.

(For more insight/more technical, see The Capital Asset Pricing Model: An Overview. "CAPM"

What Is Market Efficiency? and Working Through The Efficient Market Hypothesis. "EMH")

For a while, theoretical and empirical evidence suggested that CAPM, EMH and other rational financial theories did a respectable job of predicting and explaining certain events. However, as time went on, academics in both finance and economics started to find anomalies and behaviors that couldn't be explained by theories available at the time. While these theories could explain certain "idealised" events, the real world proved to be a very messy place in which market participants often behaved very unpredictably.

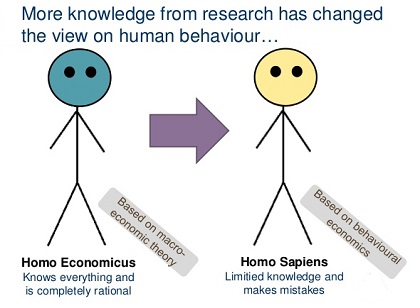

Homo Economicus

One of the most rudimentary assumptions that conventional economics and finance makes is that people are rational "wealth maximizers" who seek to increase their own well-being. According to conventional economics, emotions and other extraneous factors do not influence people when it comes to making economic choices.

In most cases, however, this assumption doesn't reflect how people behave in the real world. The fact is people frequently behave irrationally. Consider how many people purchase lottery tickets in the hope of hitting the big jackpot. From a purely logical standpoint, it does not make sense to buy a lottery ticket when the odds of winning are overwhelming against the ticket holder (roughly 1 in 146 million, or 0.0000006849%, for the famous Powerball jackpot).

Despite this, millions of people spend countless dollars on this activity.

According to my knowledge to win the Jackpot in the Austrian "6 aus 45"-lottery you ALSO need to have a lot of luck, since your odds are 1:8 Million (Austrian population).

These anomalies prompted academics to look to cognitive psychology to account for the irrational and illogical behaviors that modern finance had failed to explain. Behavioral finance seeks to explain our actions, whereas modern finance seeks to explain the actions of the "economic man" (Homo economicus).

Important Contributors

Like every other branch of finance, the field of behavioral finance has certain people that have provided major theoretical and empirical contributions. The following section provides a brief introduction to three of the biggest names associated with the field.

Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky

Cognitive psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky are considered the fathers of behavioral economics/finance. Since their initial collaborations in the late 1960s, this duo has published about 200 works, most of which relate to psychological concepts with implications for behavioral finance. In 2002, Kahneman received the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his contributions to the study of rationality in economics.

Kahneman and Tversky have focused much of their research on the cognitive biases and heuristics ( i.e. approaches to problem solving) that cause people to engage in unanticipated irrational behavior. Their most popular and notable works include writings about prospect theory and loss aversion.

Richard Thaler

While Kahneman and Tversky provided the early psychological theories that would be the foundation for behavioral finance, this field would not have evolved if it weren't for economist Richard Thaler.

During his studies, Thaler became more and more aware of the shortcomings in conventional economic theory (mostly ignoring people's behaviors).

After reading a draft version of Kahneman and Tversky's work on prospect theory, Thaler realized that, unlike conventional economic theory, psychological theory could account for the irrationality in behaviors.

Thaler went on to collaborate with Kahneman and Tversky, blending economics and finance with psychology to present concepts, such as mental accounting, the endowment effect and other biases.

Critics

Although behavioral finance has been gaining support in recent years, it is not without its critics. Some supporters of the efficient market hypothesis, for example, are vocal critics of behavioral finance.

The efficient market hypothesis is considered one of the foundations of modern financial theory. However, the hypothesis does not account for irrationality because it assumes that the market price of a security reflects the impact of all relevant information as it is released.

The most notable critic of behavioral finance is Eugene Fama, the founder of market efficiency theory. Professor Fama suggests that even though there are some anomalies that cannot be explained by modern financial theory, market efficiency should not be totally abandoned in favor of behavioral finance.

In fact, he notes that many of the anomalies found in conventional theories could be considered shorter-term chance events that are eventually corrected over time. In his 1998 paper, entitled "Market Efficiency, Long-Term Returns And Behavioral Finance", Fama argues that many of the findings in behavioral finance appear to contradict each other, and that all in all, behavioral finance itself appears to be a collection of anomalies that can be explained by market efficiency.

original link: