Related Categories

Related Articles

Articles

LTCM - Debacle (1998)

Long-Term Capital Management

Reared on Merton's and Schole's teachings of efficient markets, the professors actually believed that prices would go and go directly where the models said they should. The professors' conceit was to think that models could forecast...

... the limits of behavior...

Info about LTCM upfront:

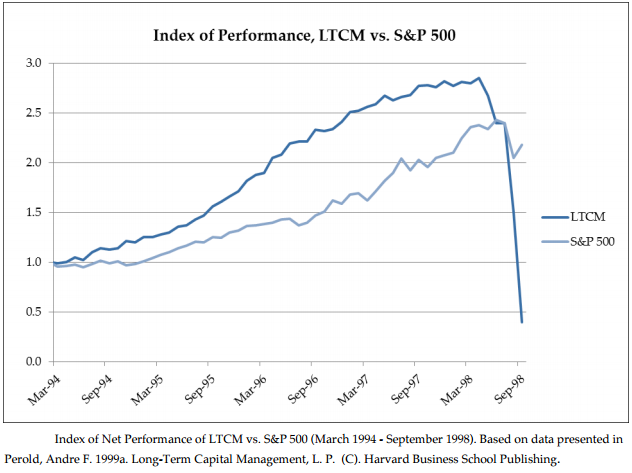

Long-Term Capital Management was a hedge fund that was started in 1994 by the legendary bond trader John Meriwether of Salomon Brothers. As a hedge fund, LTCM was more flexible than other institutions because it was exempt from certain tax and regulatory restrictions. This mobility, along with the possibility of earning profits unobtainable at any other firm, allowed Meriwether to attract an all-star team of traders and academics to the firm. Among LTCM’s partners were two Nobel Laureates, Myron Scholes and Robert Merton, as well as David Mullins, the former vice-chairman of the Federal Reserve Board. The partners’ expertise in trading bonds allowed the fund to grow rapidly; in its first four years the firm accrued $1.25 trillion in assets and grew to the size of most investment banks (MacKenzie 2003, 354).

The following are excerpts from "When Genius Failed: The Rise and Fall of Long-Term Capital Management,"

by former Wall Street Journal reporter Roger Lowenstein (longer version - available for free under the WSJ-link at the end of this posting).

As the excerpts begin, LTCM, based in Greenwich, Conn., had enjoyed a fabulous run, with nary a serious downturn.

With bond markets obligingly balmy, LTCM had quadrupled its money (before deducting fees to its partners) in a mere four years. And -as said- two of LTCM's academic superstars, Robert C. Merton and Myron S. Scholes, had recently been awarded the Nobel Prize in economics. By 1998, however, John W. Meriwether, the acclaimed trader and founder of LTCM, was increasingly troubled by the lack of opportunities in bond arbitrage, LTCM's stock in trade. Its returns for the first quarter were flat -- the fund's first dry spell -- and Wall Street traders were beginning to get nervous.

some episodes from the last months of the existence of the LTCM-Fund:

By June, spreads between bonds had begun to widen, exactly the opposite of what LTCM's computer models had forecast. In short, LTCM, relying on historical models, had bet that perceived risk would diminish, but prices were moving the opposite way. Jim McEntee, J.M.'s friend and the one partner who relied on his nose, as distinct from a computer, sensed the trade winds changing. He repeatedly urged his partners to lower the firm's risk -- lower, that is, their potent leverage and derivative exposure -- but McEntee was ignored as a nonscientific, old-fashioned gambler.

LTCM suffered a 6% loss in May and a troubling 10% drop in June. The partners insisted that losses were to be expected after their prolonged success, and predicted a speedy recovery. But then, on Aug. 17, Russia defaulted. By the end of the month, the stunned partners were frantically looking for new investors.

By Friday, August 21, traders everywhere were panicking. Stock markets in Asia and in Europe plunged. The Dow fell 280 points before noon, then recouped most of its losses. In Greenwich, on that golden late-August Friday, Long-Term's office was largely deserted. Most of the senior partners were on vacation; it was a sultry morning, and the staff was moving slowly. McEntee, the colorful "sheik" whose doleful warnings had been ignored, was minding the store. Bill Krasker, the partner who had constructed many of the firm's models, was anxiously monitoring markets, clicking from one phosphorescent page to the next. When he saw the quotation for U.S. swap spreads, a standard barometer of credit market anxiety, he stared at his screen in disbelief.

On an active day, Krasker knew, U.S. swap spreads might change by as much as a point. But on this morning, swap spreads were wildly oscillating over a range of 20 points. Krasker couldn't believe it. He sought out Matt Zames, a trader, and Mike Reisman, the firm's repo man, and heatedly broke the news. The traders hadn't seen a move like that -- ever. True, it had happened in 1987 and again in 1992. But Long-Term's models didn't go back that far. As far as Long-Term knew, it was a once-in-a-lifetime occurrence - a practical impossibility - and one for which the fund was totally unprepared.

J.M. called Jon Corzine, the chief executive of Goldman Sachs, a major Long-Term trading partner, at Corzine's home. "We've had a serious markdown," Meriwether advised him, "but everything is fine with us."

But everything was not fine. Long-Term, which had calculated with such mathematical certainty that it was unlikely to lose more than $35 million on any single day, had just dropped $553 million - 15% of its capital - on that one Friday in August. Since the end of April, it had lost more than a third of its equity.

September was even worse. And with the fund losing money day after day, the partners' spirits began to suffer.

In every class of asset and all over the world, the market moved against the hedge fund in Greenwich. The correlations had gone to one; every roll was turning up snake eyes. The mathematicians at Long-Term had not foreseen this. Random markets, they had thought, would lead to standard distributions - to a normal pattern of black sheep and white sheep, heads and tails, and jacks and deuces, not to staggering losses in every trade, day after day after day. The professors had ignored the truism - of which they were well aware - that in markets, rare events nonetheless occur.

Another article on LTCM:

Markets had been in an increasing state of panic ever since Russia had defaulted on loans in August 1998. Then, in the ensuing five weeks, LTCM suffered horrific losses, bringing it to the verge of bankruptcy. With the prospects of a forced liquidation of its assets -- which totaled a staggering USD 100 billion -- and the sudden unwinding of its trading positions, which linked it to every major financial house, William J. McDonough, president of the New York Fed, feared that markets would "possibly cease to function." Thus, on Sept. 22 and 23, Mr. McDonough orchestrated an unprecedented rescue by 14 private banks and defused the crisis.

The following are (again) excerpts from "When Genius Failed: The Rise and Fall of Long-Term Capital Management," by former Wall Street Journal reporter Roger Lowenstein.

The end of April, approximately, was the low point for bond spreads, the high point for confidence, and the high point for Long-Term Capital Management. In the manner of markets, the first hints of trouble were scattered, small and seemingly unrelated. Lloyd Blankfein, a partner at Goldman Sachs, complained to Peter Fisher, who ran trading activities at the New York Fed, that people weren't distinguishing among risks, meaning that yield differentials between riskier and less risky bonds were narrowing to the vanishing point. For the moment, everything was trading like a Treasury bill.

For Steve Freidheim of Bankers Trust, the alarm sounded during a spring trip to Singapore and Hong Kong. What Freidheim saw in Asia shook him: "A lot of big players" were taking money off the table. Freidheim returned to the United States in a pessimistic mood. "We began to short the market after that," he recalled. In the U.S., credit spreads -- that is, the premium that traders charge for less risky bonds -- had never been tighter. There was only one way for them to go, Freidheim felt, especially if the still fragile condition of Asia should become apparent.

Imperceptibly at first, other Wall Street traders started to reach similar conclusions. Banks and securities firms began to cut back their inventories of riskier, less liquid bonds -- which were the very types of bonds in Long-Term's portfolio.

By June, spreads between bonds had begun to widen, exactly the opposite of what LTCM's computer models had forecast. In short, LTCM, relying on historical models, had bet that perceived risk would diminish, but prices were moving the opposite way. Jim McEntee, J.M.'s friend and the one partner who relied on his nose, as distinct from a computer, sensed the trade winds changing. He repeatedly urged his partners to lower the firm's risk -- lower, that is, their potent leverage and derivative exposure -- but McEntee was ignored as a nonscientific, old-fashioned gambler.

Since moving to Connecticut, the partners, who no longer had to jostle with the throngs on Wall Street every day, had become even more isolated from the anecdotal, but occasionally useful, gossip that traders pass around. They found it easy to brush off McEntee's alarms, particularly since McEntee's trades had been losing money. Increasingly frustrated, McEntee met James Rickards, Long-Term's general counsel, after work one night at the Horseneck Tavern in Greenwich. Rickards was leaving the next morning on an expedition to climb Mount McKinley in Alaska. "By the time you get back, the world will have completely changed," McEntee predicted darkly.

LTCM suffered a 6% loss in May and a troubling 10% drop in June. The partners insisted that losses were to be expected after their prolonged success, and predicted a speedy recovery. But then, on Aug. 17, Russia defaulted. By the end of the month, the stunned partners were frantically looking for new investors.

By Friday, August 21, traders everywhere were panicking. Stock markets in Asia and in Europe plunged. The Dow fell 280 points before noon, then recouped most of its losses. In Greenwich, on that golden late-August Friday, Long-Term's office was largely deserted. Most of the senior partners were on vacation; it was a sultry morning, and the staff was moving slowly. McEntee, the colorful "sheik" whose doleful warnings had been ignored, was minding the store. Bill Krasker, the partner who had constructed many of the firm's models, was anxiously monitoring markets, clicking from one phosphorescent page to the next. When he saw the quotation for U.S. swap spreads, a standard barometer of credit market anxiety, he stared at his screen in disbelief.

On an active day, Krasker knew, U.S. swap spreads might change by as much as a point. But on this morning, swap spreads were wildly oscillating over a range of 20 points. Krasker couldn't believe it. He sought out Matt Zames, a trader, and Mike Reisman, the firm's repo man, and heatedly broke the news. The traders hadn't seen a move like that -- ever. True, it had happened in 1987 and again in 1992. But Long-Term's models didn't go back that far. As far as Long-Term knew, it was a once-in-a-lifetime occurrence -- a practical impossibility -- and one for which the fund was totally unprepared. One of the analysts called a trader at home and asked, "Would you like to guess where swap spreads are?" When the analyst told him, the trader snapped, "F--- you -- don't ever call me at home again!"

Nothing in any market went right that day. Long-Term lost money in Russia, Brazil -- even the U.S. stock market. The skeleton crew in Greenwich tracked Meriwether down at a dinner in Beijing, and the boss took the next flight home. Before he left, J.M. called Jon Corzine, the chief executive of Goldman Sachs, a major Long-Term trading partner, at Corzine's home. "We've had a serious markdown," Meriwether advised him, "but everything is fine with us."

But everything was not fine. Long-Term, which had calculated with such mathematical certainty that it was unlikely to lose more than $35 million on any single day, had just dropped USD 553 million - 15% of its capital - on that one Friday in August. Since the end of April, it had lost more than a third of its equity.

The following Monday, a week after Russia's default, the partners started dialing for dollars. With their gilt-edged roster of contacts, their brilliant record, their lustrous reputations, no modern Croesus was beyond their reach. Greg Hawkins tapped a friend in George Soros's fund and set up a breakfast for Meriwether, Soros and Stanley Druckenmiller, the billionaire's top strategist.

Meriwether argued, calmly but persuasively, that Long-Term's markets would snap back; for those with deep pockets, the opportunities were great. Soros listened impassively, but Druckenmiller peppered J.M. with questions. He smelled a chance to recoup Soros's recent losses in Russia. Then, Soros boldly said he would be willing to invest $500 million at the end of August -- that is, a week later -- provided that Long-Term could restore its capital by raising another $500 million in addition.

But as their losses mounted, the dream of raising money from Mr. Soros faded.

The partners began to sense that they might not make it. "We were desperate at the end of August," Eric Rosenfeld admitted. Their tone changed to disbelief and bitterness at having left themselves exposed to such needless humiliation. They were much too rich to have gotten into so much trouble.

Badly in need of a lift, Meriwether called an old friend, Vinny Mattone, who had been the fund's first contact at Bear Stearns, LTCM's clearing broker. Mattone, who had retired, was everything that J.M.'s elegant professors were not. He wore a gold chain and a pinkie ring, and he showed up at Long-Term in a black silk shirt, open at the chest. He looked as if he weighed 300 pounds. Unlike J.M.'s strangely wooden partners, Mattone saw markets as exquisitely human institutions - inherently volatile, ever-fallible.

"Where are you?" Mattone asked bluntly.

"We're down by half," Meriwether said.

"You're finished," Mattone replied, as if this conclusion needed no explanation.

For the first time, Meriwether sounded worried. "What are you talking about? We still have two billion. We have half -- we have Soros."

Mattone smiled sadly. "When you're down by half, people figure you can go down all the way. They're going to push the market against you. They're not going to roll [refinance] your trades. You're finished."

September was even worse. And with the fund losing money day after day, the partners' spirits began to suffer.

In every class of asset and all over the world, the market moved against the hedge fund in Greenwich. The correlations had gone to one; every roll was turning up snake eyes. The mathematicians at Long-Term had not foreseen this. Random markets, they had thought, would lead to standard distributions - to a normal pattern of black sheep and white sheep, heads and tails, and jacks and deuces, not to staggering losses in every trade, day after day after day. The professors had ignored the truism -- of which they were well aware - that in markets, rare events nonetheless occur.

Stuck in their glass-walled palace far from New York's teeming trading floors, they had forgotten that traders are not random molecules, or even mechanical logicians such as themselves, but people moved by greed and fear, capable of the extreme behavior and swings of mood so often observed in crowds. And in the late summer of 1998, the bond-trading crowd was extremely fearful, especially of risky credits.

Thursday, September 10 was a very bad day. Swap spreads - Long-Term's biggest bond market trade - jumped another seven points; other credit spreads widened, too. In a spot of bad luck -- or was it a portent? - a rocket ferrying a dozen Globalstar satellites fell out of the sky and exploded. Long-Term, as it happened, owned Globalstar bonds. The partners almost laughed: Even the heavens were against them. In the risk-management meeting, the traders went around the table, each reporting his results. When it became clear that every trader had lost, David Mullins, a partner and previously the U.S. Fed's vice chairman, demanded sarcastically, "Can't we ever make money - just for one day?" So far in September, they hadn't; not once.

personal stress:

Given their frayed nerves and their enormous losses, it was only human for the partners to show some tension. They were losing not only their fortunes but also their reputations. Meriwether was facing the unbearable indignity of a second disaster in a once shining career. Eric Rosenfeld, the most emotional of the group and the most devoted to the firm, was touchingly affected. At least he was not afraid to scream when the anguish overcame him. Merton, his former teacher, was upset, too; he was distraught and not himself. Worrying that Long-Term's collapse would undermine the standing of modern finance - all he had really worked for - Merton repeatedly broke into tears. The professor was wonderfully human, after all.

signature for Banks-Bail-out of LTCM needed: The Fed was expecting wires from fourteen banks totaling $3.65 billion.

The partners were ready to sign. They stood in a knot at the far end of the room, a cathedral-sized space that seemed to dwarf the small band of diminished arbitrageurs. Hilibrand was reading the contract, which was hopelessly illegible to all but the lawyers. The margins were jammed with penciled revisions and crossed-out sentences and arrows up and down, as though the contract were a visual representation of the confusion of the last three days. Rickards and a couple of other attorneys were trying to tell Hilibrand what it meant, but he didn't want to listen, he wanted to read it himself, and he could barely see it through the tears that were streaming down his face.

He didn't want to sign, he wailed; there was nothing in it for him, better to file for bankruptcy than be someone else's indentured servant with no hope of ever earning his way out. Meriwether took Hilibrand aside and talked to him about the group, and how the others were in it and needed him to be in it, and still, Hilibrand, who had never needed anyone and who had once rebelled at paying for his share of the company cafeteria but now couldn't pay his debts, refused. Then Allison talked to him and said they were trying to restore the public's faith in the system and not to destroy anybody, and J.M. said, "Larry, you better listen to Herb." And Hilibrand signed, and the fund was taken over by 14 banks.

link/article: http://www.wsj.com

.pdf/download: https://courses.cit.cornell.edu (.pdf)