Related Categories

Related Articles

Articles

Anleihen vs. Aktien

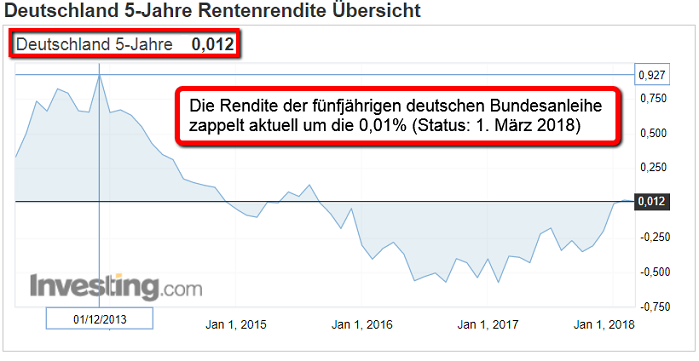

"Reminder": Wer Deutschland heute 5 Jahre Geld leihen will, zahlt -nach Inflation- wohl drauf...Dies kann man ganz klar an der Entwicklung der Renditen der 5-jährigen Bundesanleihen ablesen. Was hätte damals im Jahr 2012 Warren Buffet zu solch einem "ähnlichen...

...US-Tatbestand gesagt?" Well, please go on and read his short essay on that topic (extract from his most recent shareholder letter 2017):

When Future Returns of an Existing Investment Drop to Unattractive Levels, Sell and Reinvest The Proceeds Elsewhere (so the potential conclusion of following extract):

Many readers are familiar with Warren Buffett's bet against hedge funds. In this bet, Buffett bet USD 1 million that an S&P 500 Index ETF would outperform a selection of hedge funds over a ten-year period.

Buffett was right - the S&P 500 trounced the performance of the funds selected by Buffett's counterparty Protégé Partners. Buffett revisited this bet in the 2017 Letter to Shareholders to illustrate an interestingly unrelated point – that when the expected returns of one of your existing investments falls to unattractive levels, you should sell the investment and reinvest the proceeds in more appealing investment opportunities.

Here's what Buffett writes on the subject:

" [...] As the name implies, the bonds we acquired paid no interest, but (because of the discount at which they were purchased) delivered a 4.56% annual return if held to maturity. Protégé and I originally intended to do no more than tally the annual returns and distribute USD 1 million to the winning charity when the bonds matured late in 2017.

After our purchase, however, some very strange things took place in the bond market. By November 2012, our bonds - now with about five years to go before they matured - were selling for 95.7% of their face value. At that price, their annual yield to maturity was less than 1%. Or, to be precise, zero .88%.

Given that pathetic return, our bonds had become a dumb - a really dumb - investment compared to American equities. Over time, the S&P 500 - which mirrors a huge cross-section of American business, appropriately weighted by market value - has earned far more than 10% annually on shareholders' equity (net worth).

In November 2012, as we were considering all this, the cash return from dividends on the S&P 500 was 2.5% annually, about triple the yield on our U.S. Treasury bond. These dividend payments were almost certain to grow. Beyond that, huge sums were being retained by the companies comprising the 500. These businesses would use their retained earnings to expand their operations and, frequently, to repurchase their shares as well. Either course would, over time, substantially increase earnings-per-share. And - as has been the case since 1776 - whatever its problems of the minute, the American economy was going to move forward.

Presented late in 2012 with the extraordinary valuation mismatch between bonds and equities, Protégé and I agreed to sell the bonds we had bought five years earlier and use the proceeds to buy 11,200 Berkshire "B" shares. The result: Girls Inc. of Omaha found itself receiving USD 2,222,279 last month rather than the USD 1 million it had originally hoped for.

Berkshire, it should be emphasized, has not performed brilliantly since the 2012 substitution. But brilliance wasn't needed: After all, Berkshire's gain only had to beat that annual .88% bond bogey - hardly a Herculean achievement.

The only risk in the bonds-to-Berkshire switch was that year-end 2017 would coincide with an exceptionally weak stock market. Protégé and I felt this possibility (which always exists) was very low. Two factors dictated this conclusion: The reasonable price of Berkshire in late 2012, and the large asset build-up that was almost certain to occur at Berkshire during the five years that remained before the bet would be settled. Even so, to eliminate all risk to the charities from the switch, I agreed to make up any shortfall if sales of the 11,200 Berkshire shares at yearend 2017 didn-t produce at least USD 1 million.

Investing is an activity in which consumption today is foregone in an attempt to allow greater consumption at a later date. "Risk" is the possibility that this objective won't be attained.

By that standard, purportedly "risk-free" long-term bonds in 2012 were a far riskier investment than a longterm investment in common stocks. At that time, even a 1% annual rate of inflation between 2012 and 2017 would have decreased the purchasing-power of the government bond that Protégé and I sold.

I want to quickly acknowledge that in any upcoming day, week or even year, stocks will be riskier - far riskier - than short-term U.S. bonds. As an investor's investment horizon lengthens, however, a diversified portfolio of U.S. equities becomes progressively less risky than bonds, assuming that the stocks are purchased at a sensible multiple of earnings relative to then-prevailing (!) interest rates (!!)

Exclamation marks added by myself (Ralph Gollner)

It is a terrible mistake for investors with long-term horizons - among them, pension funds, college endowments and savings-minded individuals - to measure their investment "risk" by their portfolio's ratio of bonds to stocks. Often, high-grade bonds in an investment portfolio increase its risk.

A final lesson from our bet: Stick with big, "easy" decisions and eschew activity. During the ten-year bet, the 200-plus hedge-fund managers that were involved almost certainly made tens of thousands of buy and sell decisions. Most of those managers undoubtedly thought hard about their decisions, each of which they believed would prove advantageous. In the process of investing, they studied 10-Ks, interviewed managements, read trade journals and conferred with Wall Street analysts.

Protégé and I, meanwhile, leaning neither on research, insights nor brilliance, made only one investment decision during the ten years. We simply decided to sell our bond investment at a price of more than 100 times earnings (95.7 sale price/.88 yield), those being "earnings" that could not increase during the ensuing five years.

Please think about that last para mentioning the freaking Bond-valuation (similar now to German BUNDs !!) - comment by myself (Ralph Gollner)

We made the sale in order to move our money into a single security - Berkshire - that, in turn, owned a diversified group of solid businesses. Fueled by retained earnings, Berkshire's growth in value was unlikely to be less than 8% annually, even if we were to experience a so-so economy.

After that kindergarten-like analysis, Protégé and I made the switch and relaxed, confident that, over time, 8% was certain to beat .88%. By a lot."

The most obvious takeaway from this passage is that when the potential returns of an investment drop, you should be willing to sell the security and reinvest the proceeds elsewhere.

"Sometimes" one should just favor inactivity when debating whether to make trades in ones investment portfolio...

links:

Berkshire - .pdf

www.berkshirehathaway.com/2017ar/2017ar.pdf